When Trauma Becomes Transformation

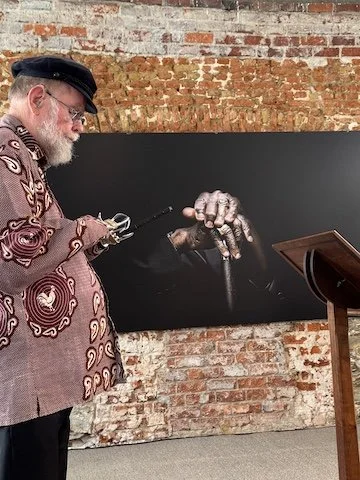

This past Saturday, I had the privilege of hearing Father Michael Lapsley speak at the Desmond & Leah Tutu Museum in Cape Town, South Africa. Our group of Portland Seminary doctoral students gathered in a room resonating with memory and courage, listening to a man who has literally lived through fire.

Born in New Zealand in 1949 and ordained in Australia, Father Lapsley joined the Society of the Sacred Mission and came to South Africa in 1973. He worked with both black and white students during the height of apartheid, serving as chaplain in Durban. When the 1976 Soweto Uprising broke out, he spoke boldly against the repression of schoolchildren, and his outspokenness led to exile.

Lapsley moved first to Lesotho and then to Zimbabwe, where he continued to minister. And on April 28, 1990 -- just three months after Nelson Mandela’s release from prison -- his life changed irreparably.

As he sat on his couch, catching up on correspondence, he noticed one package that contained two Christian magazines, one in Afrikaans and one in English. Nothing seemed unusual. But as Father Lapsley opened the English one, the two magazines exploded; a bomb had been hidden between them by supporters of the apartheid regime.

The blast threw him backwards, exploding both of his hands, his right eye, and his eardrums, and leaving him with severe burns across his body. He remembers being unable to see, unable to hear, and experiencing pain he did not know was humanly possible. Later in the hospital, Lapsley began to realize the extent of his injuries: “I had accepted that I might die because of the side I had chosen,” he said, “but not that I would live with such disability. For a short time, I wished I were dead. I had never met someone without hands, so I did not think I could live an active life again.”

But survival became the beginning of a new calling. After months of surgeries and painful rehabilitation, Lapsley returned to South Africa in 1992. He became chaplain at the Trauma Centre for Victims of Violence and Torture in Cape Town, working alongside the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In 1998, he founded the Institute for Healing of Memories, which now serves people worldwide: survivors of apartheid, war, genocide, imprisonment, displacement, and disease.

When he spoke with us last Saturday, Lapsley shared wisdom forged in suffering: “All have been traumatized,” he said. “All have a story to tell.” But he prefers the word woundedness instead of the word trauma, because woundedness holds both pain and possibility: “Part of my victory,” he said, “is living as joyfully as I can.”

And healing, he reminded us, is not the end: Healing leads to discipleship. We are restored so that we might live fully and help others do the same. Lapsley described the journey from victim to survivor to victor, and wisely warned: “Trauma is either transformed or transmitted.”

He named painful realities -- how patriarchy produces “damaged men who damage women,” how South Africa failed to prosecute perpetrators after apartheid -- yet also celebrated that no other country has confronted its violent past so directly in the very generation that suffered it.

Most memorable were the questions he left us with:

How have you healed your own woundedness?

How have you made the world a gentler place?

How have you helped to heal Mother Earth?

Finally, Lapsley reminded us that some healing happens only in community: “People become the healers of one another.”

As I listened, I thought of our Cedar Creek Church family. Each of us carries wounds; some are visible, others hidden. But in Christ, woundedness is never the last word. Healing is possible. Transformation is possible. And God calls us to be healers in the lives of others.

May Father Lapsley’s testimony stir us to deeper vulnerability, deeper listening, and deeper commitment to restorative work -- not only in our own hearts, but among one another and in our wider community.